Title Outbreak of Naegleria fowleri in Kerala, India, 2025

Authors Vishwa Desai, Atalay Goshu Muluneh, Aye Moa

Date of first report of the outbreak On the 16th of March 2025, Kerala’s Directorate of Health Services reported six confirmed cases of Naegleria fowleri (1)

Disease or outbreak Exposure to Naegleria fowleri (N fowleri) can lead to Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM)(2).

Origin (country, city, region) Multidistrict, Kerala, India (3).

Suspected Source (specify food source, zoonotic or human origin or other) Naegleria fowleri is contracted through environmental exposure, commonly found in warm, freshwater bodies such as lakes, rivers or untreated water wells (4). Definite sources are yet to be confirmed; the scattered distribution of cases has prompted health officials to investigate local water systems and increase chlorination of wells (2).

Date of outbreak beginning The current outbreak began on March 16th, 2025. However, sporadic cases of N fowleri have been reported since the beginning of 2025 (1)

Date outbreak declared over This outbreak is ongoing as of the 31st of October 2025, as cases continue to be reported (5).

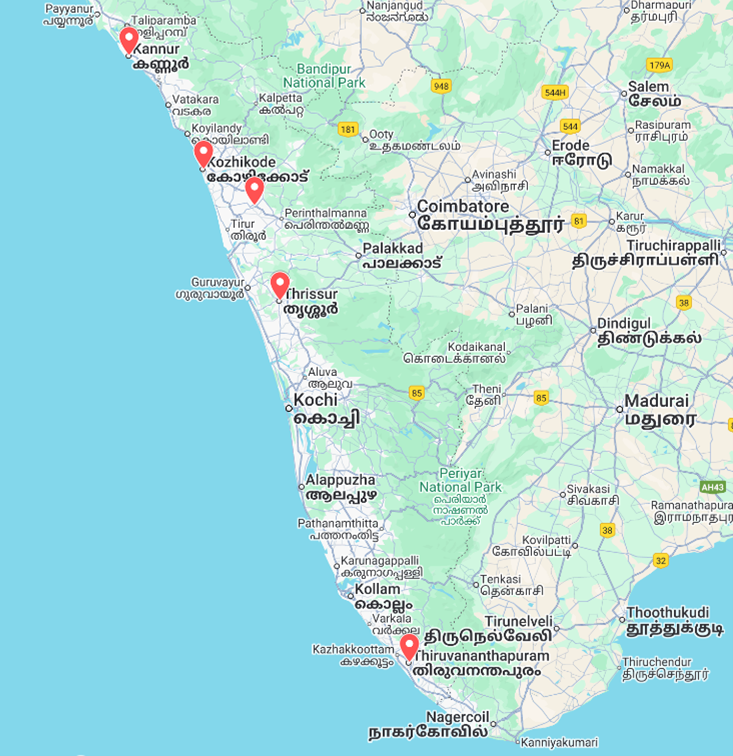

Affected countries and regions As of October 31st, there have been cases reported in Kozhikode, Malappuram, Kannur, Thiruvananthapuram, and Thrissur (6-10). Thiruvananthapuram has reported the highest number of 48 cases and seven deaths (11). As represented by the red pins of Figure 1, the reported outbreak signals follow the border areas near the ocean (Figure 1) (12-15).

Figure 1: The red pins represent locations of Naegleria fowleri outbreaks, Kerala (12-15).

Figure 1: The red pins represent locations of Naegleria fowleri outbreaks, Kerala (12-15).

Number of cases (specify at what date if ongoing) As of October 31, 2025, 153 confirmed cases and 33 confirmed deaths have been reported in Kerala as a result of N fowleri exposure (5). This brings a case fatality rate of 21.6%.

Clinical features Naegleria fowleri is a free-living thermophilic amoeba found globally, usually in warmer climates with heavy rainfall (16). N fowleri infections in humans cause primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) by travelling up the nasal cavity and infecting the central nervous system (CNS) (16).

If inhaled when in its trophozoite state, N fowleri will travel from the nasal cavity to the olfactory bulbs via the olfactory nerve (17). The amoeba can only infect the CNS of an individual if travelling through the olfactory route, not orally (18). Once in the brain, the pathogen causes haemorrhagic necrosis, resulting in PAM characterised by cerebral oedema, acute inflammation and tissue destruction (17).

The structure of N fowleri is characterised by two main parts, the food-cup surface structure, which digests brain tissue and its ability to release cytolytic toxins, which induce cell death (18). Furthermore, the introduction of the trophozoites into the CNS activates an aggressive immune response, which further exacerbates the necrosis of the brain (18).

The incubation period is 1-14 days, after which symptoms start to present rapidly (19). Headache, fever, nausea, and vomiting represent the most common initial presentations (19). These early signs resemble typical viral or bacterial meningitis symptoms (20). Later clinical features include neck rigidity, lethargy, confusion, disorientation, seizures, and cranial nerve abnormalities (20).

PAM is officially diagnosed through observing the individual’s cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which will contain N fowleri (17). To confirm the presence of the trophozoites, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is conducted with the CSF to detect N fowleri DNA (16).

The majority of infected individuals die within 3- 12 days of being exposed to N fowleri if not treated immediately (16). As there are no specific clinical presentations of PAM, patients tend to be diagnosed post-mortem by conducting a brain biopsy which reveals haemorrhagic meningitis predominantly in the olfactory bulbs (16,18).

Mode of transmission (dominant mode and other documented modes) Direct intranasal exposure through inhalation of contaminated freshwater (21). The most noted mode is through swimming, diving, or other water-related activities in warm bodies of freshwater (16). N fowleri is not transmissible through person-to-person contact (2). Additionally, exposure to the amoeba can occur through domestic water-related activities such as bathing and nasal irrigation.

A 2020 study in Pakistan found that out of the 146 cases of N fowleri detected from 2008 to 2019, only two individuals had recently performed recreational, water-related activities (22). All infected individuals were Muslim, so the suggested sources of exposure were domestic water supplies, which were used to conduct ablution (22).

Demographics of cases N fowleri cases are reported worldwide and typically affect immunocompetent children and young adults (23). Geographically, the amoeba tends to be detected near the equator; however, its range is expanding with increasing global temperature (24).

In contrast, the Kerala outbreak portrays no consistent age group that is more likely to be exposed, and there is insufficient data to provide information on sex-related demographics. The ages of the affected individuals in this outbreak range from 3 months to 90 years (8,14,25).

Case fatality rate As of 2023, only 488 cases of N fowleri infections have been reported since 1962 (2). The CDC reported N fowleri infections, with a general fatality rate of 97% (26). The mortality rate for this current outbreak is significantly lower at 21.6% for the period January 1st to October 31st (33 deaths among 153 reported cases). The increase in survival rates has been attributed to early detection and treatment, as Kerala continues to improve district-level diagnostic systems (12).

Complications Symptoms of PAM are hyperacute, with headaches, nausea and fever presenting 1-14 days after exposure (17). The clinical presentation of PAM often resembles bacterial meningitis (2). PAM is rapidly progressive, with rapid neurological deterioration, cerebral oedema, brain herniation, seizures, coma, and ultimately death occurring within days of symptom onset (27). In this current outbreak, patients have presented with aligning symptoms (6,8,13,14,23,28,29).

Due to factors such as insignificant characteristics of onset symptoms and the rarity of infections, the efficient diagnosis of N fowleri is slim (2). Furthermore, diagnostic facilities specific to testing for N fowleri are sparse in most countries, thus confirmation of exposure is quite often delayed (16). Among the rare survivors of PAM, there is a high chance that severe neurological sequelae may be observed if treatment is delayed, as seen in an 8-year-old male who was not treated until 120 hours after the onset of symptoms (30).

Available prevention No prophylactic drugs are currently available to prevent Naegleria fowleri (31). Prevention strategies to reduce infection include avoiding swimming or bathing in warm, stagnant, freshwater sources such as lakes and rivers (32). Additional measures include using nasal clips and maintaining head position above the water level (4,26).

Water source contamination can be mitigated through the routine monitoring of freshwater bodies and chlorination of wells, storage tanks, and public bathing facilities (32). Globally, a free chlorine level of at least 2.0 mg/L is recommended to eliminate N fowleri from water storage systems, this is a general and preventive measure that would be most applicable in regions with a known N fowleri presence, such as Kerala, specifically in water tanks and distribution facilities (4,33).

Available treatment Current knowledge on the treatment of N fowleri is based on case reports and in vitro studies on animals (21). Recommendations from the CDC involve administering a mix of amphotericin B, fluconazole, rifampin, miltefosine, azithromycin, and dexamethasone intravenously or intrathecally (34). Early detection of the pathogen and treatment greatly reduces the chance of fatality due to the rapid progressive nature of the infection (21).

Between 1971 and 2023, eight laboratory-confirmed cases of survival were documented amongst 381 reported cases in the United States, Mexico, Australia and Pakistan (35). The age distribution of survivors ranged from 5 to 22 years, with 7 of the 8 cases (87.5%) occurring in males (35). Diagnosis occurred within 5 days of the onset of initial symptoms, after which all patients received antimicrobial therapy.

The drugs administered included intravenous amphotericin B (100%), oral rifampicin (87.5%), intravenous fluconazole (75%), oral miltefosine (50%), intravenous azithromycin (50%), and miconazole, sulfisoxazole, and dexamethasone (12.5%) (27,31,35).

A 2015 case study showed the successful treatment of a 12-year-old female in Arkansas, USA, who was diagnosed with PAM after being exposed to N fowleri in a waterpark (27). Treatment success was attributed to lowering intracranial pressure and the administration of miltefistone 36 hours after initial diagnosis (27). This case applied the successful use of induced hypothermia to reduce the effects of intercranial pressure, cytolytic toxins and apoptosis (27).

Comparison with past outbreaks Since discovery in 1962, more than 500 cases of infections caused by Naegleria fowleri have been diagnosed across 39 countries, with the majority occurring in the USA, India, Pakistan, and Australia (2). Between 1962 and 2014, 260 cases were reported, with only 11 infected individuals surviving (2).

The United States of America has documented the highest rates of diagnoses, with 157 cases being reported (1962-2022) (24). Outbreaks generally occurred in southern states; however, cases have emerged in Minnesota (2010), Kansas (2011) and Indiana (2012) (2). Factors, including contaminated swimming pools and water management systems, and freshwater environments, are linked to these outbreaks (2).

143 cases of N fowleri infections were reported in Pakistan (2023), most of which occurred in Karachi (2). Monsoon season, causing heavy rainfall and high humidity alongside inadequately treated water supplies, was identified as the cause of the increased infection rates (2). Additionally, several cases were linked to individuals who performed ablution before prayer (2). Currently, it is estimated that 20 PAM-related deaths occur annually in Karachi (24).

Naegleria fowleri was first identified in Kerala in 2016 (2). In 2024, 36 cases and nine associated deaths were reported in Kerala (2). Like Pakistan, Kerala has experienced increased rainfall and a rise in temperatures, which may have impacted the ongoing outbreaks (2). Although clear sources of contamination have not been discovered, examination of previous outbreaks suggests that contaminated freshwater sources, including wells, ponds, and water storage systems used for domestic purposes, may be contributing to infection in Kerala (24).

Since January 2025, 153 cases of N fowleri have been confirmed, more than four times the number of cases in 2024 (12). Environmental factors such as elevated temperatures and altered precipitation patterns should be considered. Additionally, increased detection facilities and clinical awareness may suggest selection bias (36).

Unusual features The Kerala outbreak has a distinctive epidemiological pattern when compared to the past N fowleri cases. Whilst previous outbreaks demonstrated clear clustering with cases linked to identifiable common water sources, Kerala presents as geographically dispersed, isolated incidents without apparent epidemiological connections (12). As noted by health authorities, these single, isolated cases have substantially complicated epidemiological investigations, as traditional contact tracing and source identification methods prove less effective (15). Furthermore, the incidence rate is significantly higher than the expected number of cases of primary amoebic meningoencephalitis. Global surveillance data indicate an annual average of 0-8 cases in most reporting countries, with PAM classified as a rare infection (24).

The global median age of infection is 14 years, with an age range of 1 month to 85 years (24). For this outbreak, the age distribution of confirmed cases ranges from 3 months to 90 years, encompassing a broader age range [2,3]. About 50-85% of cases occur in individuals aged 5-24 years, predominantly males, who engage in aquatic recreational activities (36). The Kerala outbreak includes cases in very young infants and elderly individuals, populations with presumably limited participation in high-risk water sports (12).

The case fatality rate in this outbreak appears reduced compared to the established global mortality rate of approximately 97% for PAM (2). Potential contributing factors include earlier case detection due to increased clinical awareness, expedited diagnostic confirmation, prompt initiation of antimicrobial therapy, and access to intensive neurological care (12,19,36).

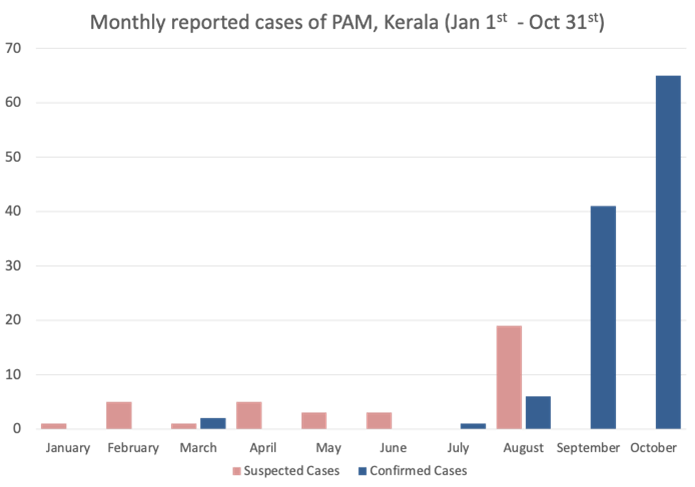

Critical analysis Data from the Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme (IDSP), managed by Kerala’s Directorate of Health Services and the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), were used to show the number of suspected and confirmed cases of N fowleri in Kerala from January to October this year.

Figure 2: Monthly reported cases of PAM, Kerala (Jan 1st - Oct 31st)

Figure 2: Monthly reported cases of PAM, Kerala (Jan 1st - Oct 31st)

Data source: Integrated Diseases Surveillance Program, NCDC (5).

Figure 2. Demonstrates the seasonal surge in cases as the monsoon season ends in September. From January through July, case numbers remained relatively low and sporadic. At the beginning of August, we observe a sharp escalation, with cases peaking in October at 65, the highest monthly case count in this period (3). The shift from suspected cases to predominantly confirmed cases from August onward suggests improved clinical awareness, but also awareness of the infection within the community, as the outbreak intensified (36). The temporal clustering strongly indicates environmental or behavioural factors associated with the monsoon season and warmer months. September and October alone account for approximately 105 of the 153 total cases.

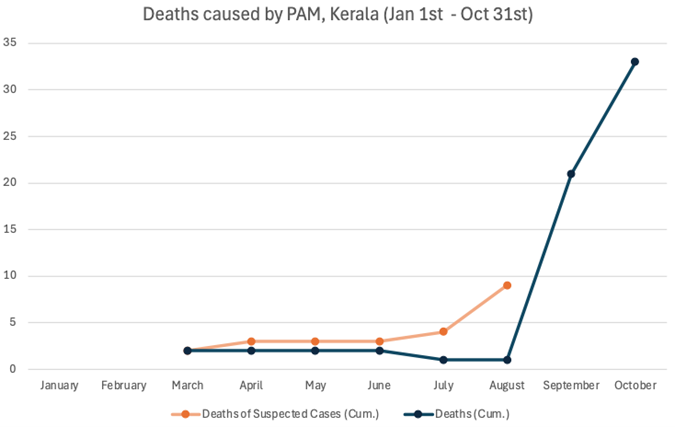

Figure 3: Cumulative Deaths caused by PAM, Kerala (Jan 1st - Oct 31st).

Figure 3: Cumulative Deaths caused by PAM, Kerala (Jan 1st - Oct 31st).

Data source: Integrated Diseases Surveillance Program, NCDC (5).

The death toll over the same 10-month period remained relatively stable at approximately two confirmed deaths from January through August. However, there was an increase beginning in September, with confirmed deaths rising from 1 to 33 by October 31st. Deaths of suspected cases are defined by individuals who have passed before the diagnosis of PAM was confirmed. Suspected deaths accumulated gradually throughout the year, reaching nine by August. This suggests either delays in laboratory confirmation or initial under recognition and underdiagnosis of PAM as the cause of death (12). In September, the confirmed deaths overtook suspected deaths, indicating improved case ascertainment and diagnostic confirmation during the peak outbreak period. With 33 confirmed deaths from 153 confirmed cases, this yields approximately a 21.6% case fatality rate in this cohort, which is significantly lower than the typically reported 97% fatality rate (26).

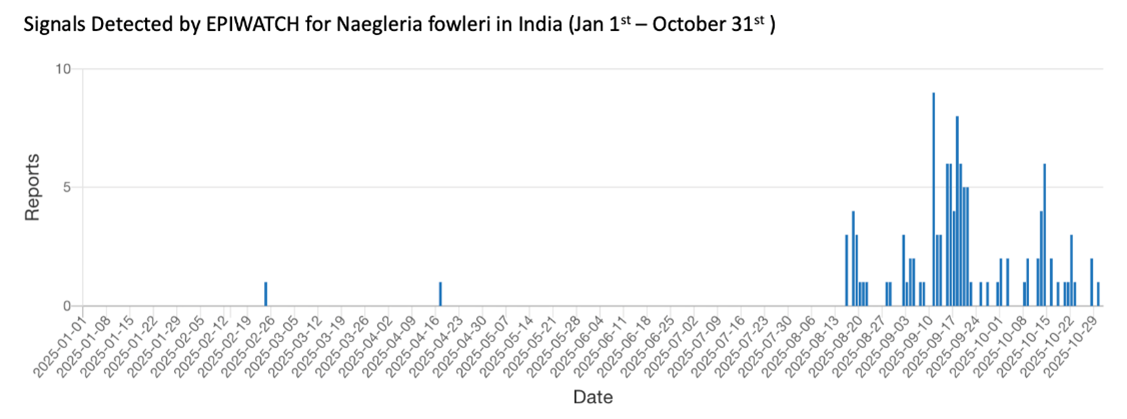

Figure 4: Signals Detected by EPIWATCH® for Naegleria fowleri in India (Jan 1st – October 31st).

Figure 4: Signals Detected by EPIWATCH® for Naegleria fowleri in India (Jan 1st – October 31st).

Data source: EPIWATCH® (37).

EPIWATCH® is an artificial intelligence-based early warning system established in 2016, facilitating the detection and monitoring of emerging outbreaks or infections ahead of formal surveillance reports by health authorities (29). Signals Detected by EPIWATCH® for N fowleri in India from January 1st - October 31st provides insight on the emerging outbreak of N fowleri in Kerala, as shown in figure 4. EPIWATCH® detected a signal for N fowleri in Kerala on the 24th of February, whilst the Health and Welfare Department of Kerala officially confirmed outbreaks on March 16th. Although not directly comparable to IDSP case data, the findings highlight that EPIWATCH® identified an emerging increase in infections in Kerala from September, with signals appearing approximately two weeks earlier, in mid-August. This pattern suggests that media attention intensified approximately 2 weeks before the clinical case peak, as observed in the IDSP data. The sustained high frequency of signals detected through September and October, with multiple reports per day, reflects the growing public awareness and concern about the outbreak (30). So far, no other international surveillance reports or health agencies, such as the WHO or the CDC, have reported on this ongoing outbreak in Kerala.

The decrease in case fatalities in this outbreak can be linked to improvements in regional healthcare systems and an increase in diagnostic capacity. In response to rising incidence rates in 2024 compared to previous years, Kerala upgraded its diagnostic facilities, establishing PCR testing in Thiruvananthapuram, which can identify N fowleri (36) . Before, specimens were sent to Chandigarh for verification, creating diagnostic delays (36). Kozhikode has the capabilities to conduct cerebrospinal fluid microscopic examination and commence treatment protocols before receiving PCR confirmation (36).

Establishing district-level facilities has shortened the interval between clinical presentation and the commencing anti-microbial therapy, resulting in faster clinical intervention and potentially accounting for enhanced survival rates (36). Additionally, the rising number of documented cases may reflect the improved surveillance mechanisms rather than disease escalation, implying previous under detection caused by inadequate diagnostic infrastructure or the incorrect classification of PAM as bacterial meningitis (38).

Several factors contribute to this outbreak's emergence and scale. Kerala's tropical climate, with extended warm seasons, creates ideal conditions for amoeba growth. Monsoon patterns deliver heavy rainfall, followed by hot, humid weather, as seen in 2024, which promotes Naegleria proliferation (39). Global rising temperatures and altered precipitation patterns associated with climate change may be creating more favourable conditions for Naegleria fowleri proliferation in freshwater bodies (40). In its thermophilic state, the amoeba thrives in warm water temperatures (25-46°C), and extended periods of elevated water temperatures may be expanding both the geographical range and seasonal window for human exposure (2,24).

Kerala's tropical climate, combined with recent meteorological patterns, may be contributing to the sustained presence of amoeba in water sources previously considered low risk.

The ongoing outbreak suggests the involvement of multiple water sources, potentially indicating widespread environmental contamination. This pattern raises concerns about water infrastructure quality, including inadequately maintained freshwater bodies, contaminated bore wells or domestic water storage systems (16). The case demographic of very young infants and elderly individuals suggests exposure through domestic water use, rather than recreational activities alone (12). The state's extensive freshwater systems present a significant exposure risk. With almost 56 thousand freshwater bodies and 91.5% of water bodies used for irrigation, domestic, drinking, and recreational purposes, there's widespread human-water contact (41). Critically, 62% of the population, which is approximately 6.5 million people, relies on open wells, which are particularly vulnerable to contamination (41).

With the increasing rate of global N fowleri detections, further research is needed to improve our understanding of the amoeba's aetiology and the efficacy of treatment procedures. Case reports of survivors indicate that treatment plans are often established empirically (27). Thus, clinical trials should be done to establish valid treatment protocols. However, due to the rarity of global case numbers and the ethical considerations involved, conducting such research poses significant challenges.

Key questions

1. What factors have created such a surge in cases?

2. Out of the surviving individuals infected with PAM, what aligning treatment strategies have been applied?

3. As infection rates increase globally, will progress be made in establishing clinical trials to develop treatments for PAM?

4. What factors may have contributed to the decrease in mortality rates from a N fowleri infection?

5. With the effects of climate change growing, will N fowleri become more prevalent?

Funding support

AM and AGM are supported by the Microsoft Accelerating Foundation Models Research (AFMR) grant program.

1. Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme K. IDSP Daily Report 16.03.2025. Kerala, India: Directorate of Health Services, Government of Kerala; 2025 16th March 2025.

2. Alanazi A, Younas S, Ejaz H, Alruwaili M, Alruwaili Y, Mazhari BBZ, et al. Advancing the understanding of Naegleria fowleri: Global epidemiology, phylogenetic analysis, and strategies to combat a deadly pathogen. J Infect Public Health. 2025;18(4):102690.

3. Surge in amebic meningoencephalitis in Kerala: 65 cases and 12 deaths in October, bringing the 2025 total to 153 cases and 33 deaths Beacon: Beacon; 2025 [Available from: https://beaconbio.org/en/report/?reportid=8ecc55b9-9f31-4308-a597-26a8d98ce77d&eventid=2b3edcfe-7247-4b6f-9ee5-4a749fbd6ed7.

4. Health N. Naegleria fowleri fact sheet: NSW Health; 2017 [updated 05/04/2017.

5. Integrated Disease Surveillance Programme K. IDSP Daily Report 31.10.2025. Kerala, India: Directorate of Health Services, Government of Kerala; 2025 31st October 2025.

6. Goswami S. Surge In Deadly Brain-Eating Amoeba Cases In Kerala: Why And How It Spreads. NDTV. 2025.

7. Singh MK. Kozhikode Health Alert: Preventing Brain-Eating Amoeba: Continental Hospitals; 2025 [Available from: https://continentalhospitals.com/blog/kozhikode-health-alert-preventing-brain-eating-amoeba/.

8. Biswas S. Battling a rare brain-eating disease in an Indian state. BBC. 2025.

9. Service EN. Kerala reports 11th case of amoebic brain infection as 10-year-old boy from Malappuram tests positive. The New India Express. 2025.

10. Thrissur native dies of amoebic meningoencephalitis at Kozhikode MCH, 9 under treatment Onmanorama. 2025.

11. Network) BBaEAC. Surge in amebic meningoencephalitis in Kerala: 65 cases and 12 deaths in October, bringing the 2025 total to 153 cases and 33 deaths: BEACON; 2025 [Available from: https://beaconbio.org/en/report/?reportid=8ecc55b9-9f31-4308-a597-26a8d98ce77d&eventid=2b3edcfe-7247-4b6f-9ee5-4a749fbd6ed7.

12. Asokan S, Choudekar, A., V, M., Sm, R., Abbas, R. K., Hadi, Z. S., Vijayan, S., Atiyah, M. M., Rajeswary, D., and Cherian, T. Amoebic meningoencephalitis in Kerala: Insights for strengthening global health preparedness. Mass Gathering Medicine. 2025;4.

13. Desk TL. 80 cases, 21 deaths in Kerala due to brain-eating infection: How fresh stagnant water can cause this deadly disease. Times of India. 2025 24/09/2025.

14. Everett M. Alarm in India’s Kerala as cases of ‘brain-eating’ amoeba rise. Al Jazeera. 2025 18/09/2025.

15. Marchenko S. A new deadly brain-eating infection is spreading in India, and it's not mother-in-law. Todayua. 2025 22/09/2025.

16. Pervin N, Sundareshan V. Naegleria Infection and Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL)2025.

17. Mitra A, Goulart DB. From nose to neurons: The lethal journey of the brain-eating amoeba. Microbe-Neth. 2025;8.

18. Jahangeer M, Mahmood Z, Munir N, Waraich UE, Tahir IM, Akram M, et al. Naegleria fowleri: Sources of infection, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management; a review. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;47(2):199-212.

19. Siddiqui R, Maciver SK, Khan NA. Naegleria fowleri: emerging therapies and translational challenges. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2025;23(9):753-61.

20. Hamaty E, Jr., Faiek S, Nandi M, Stidd D, Trivedi M, Kandukuri H. A Fatal Case of Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis from Recreational Waters. Case Rep Crit Care. 2020;2020:9235794.

21. Grace E, Asbill S, Virga K. Naegleria fowleri: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment options. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2015;59(11):6677-81.

22. Ali M, Jamal SB, Farhat SM. Naegleria fowleri in Pakistan. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):27-8.

23. Lona G. ‘Brain-eating amoeba' kills 19 people in India’. Planet News. 2025 21/09/2025.

24. Gharpure R, Bliton J, Goodman A, Ali IKM, Yoder J, Cope JR. Epidemiology and Clinical Characteristics of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Caused by Naegleria fowleri: A Global Review. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(1):e19-e27.

25. Kerala’s brain-eating amoeba that enters through nose has 97% fatality rate; only 20 survived globally till date. The Economic Times. 2025 19/09/2025.

26. CDC. Naegleria fowleri Infections: CDC; 2025 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/naegleria/about/.

27. Linam WM, Ahmed M, Cope JR, Chu C, Visvesvara GS, da Silva AJ, et al. Successful treatment of an adolescent with Naegleria fowleri primary amebic meningoencephalitis. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):e744-8.

28. Geddes L. Everything you need to know about the brain-eating amoeba that’s killed three children in Kerala: Gavi; 2024 [updated 18/07/2024.

29. Ghosh D. Kerala reports nearly 80 cases, 21 deaths due to brain-eating amoeba; know how it spreads, preventive measures. India TV News. 2025.

30. Vareechon C, Tarro T, Polanco C, Anand V, Pannaraj PS, Dien Bard J. Eight-Year-Old Male With Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(8):ofz349.

31. Vargas-Zepeda J, Gomez-Alcala AV, Vasquez-Morales JA, Licea-Amaya L, De Jonckheere JF, Lares-Villa F. Successful treatment of Naegleria fowleri meningoencephalitis by using intravenous amphotericin B, fluconazole and rifampicin. Arch Med Res. 2005;36(1):83-6.

32. Clinic C. Brain-Eating Amoeba: Cleveland Clinic; 2022 [updated 29/11/2022.

33. Bristow Sa. Naegleria fowleri Detected in Queensland Water Supply: Simmonds and Bristow; [Available from: https://www.simmondsbristow.com.au/naegleria-fowleri-detected-in-queensland-water-supply/.

34. Kim JH, Jung SY, Lee YJ, Song KJ, Kwon D, Kim K, et al. Effect of therapeutic chemical agents in vitro and on experimental meningoencephalitis due to Naegleria fowleri. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(11):4010-6.

35. Burqi AMK, Satti L, Mahboob S, Anwar SOZ, Bizanjo M, Rafique M, Ghanchi NK. Successful Treatment of Confirmed Naegleria fowleri Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30(4):803-5.

36. KERALA GO. Action Plan to optimize the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Amoebic Meningoencephalitis in Kerala. In: Department HFW, editor. Thiruvananthapuram: HEALTH and FAMILY WELFARE (F) DEPARTMENT; 2024.

37. EPIWATCH. EPIWATCH®: EPIWATCH®; 2025 [Available from: https://www.epiwatch.org/.

38. Gajula SN, Nalla LV. Fighting with brain-eating amoeba: challenges and new insights to open a road for the treatment of Naegleria fowleri infection. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2023;21(12):1277-9.

39. M. Mohapatra RKJ, and Satya Prakash. Monsoon 2024: A Report. In: Department IM, editor. NEW DELHI, India: India Meteorological Department; 2024.

40. Herriman R. Naegleria fowleri in Sindh province, Pakistan and Kerala state, India. Outbreak News Today. 2025 14/09/2025.

41. Aju CD, Achu AL, Mohammed MP, Raicy MC, Gopinath G, Reghunath R. Groundwater quality prediction and risk assessment in Kerala, India: A machine-learning approach. J Environ Manage. 2024;370:122616.

.