Title Outbreak of Chikungunya in Foshan, China, 2025

Authors Pan Zhang, Dr Noor Bari, and Dr Ashley Quigley

Date of first report of the outbreak July 8, 2025 (1)

Disease or outbreak Chikungunya

Origin (country, city, region) Shunde District, Foshan City, Guangdong Province, China

Suspected Source (specify food source, zoonotic or human origin or other) Chikungunya is a mosquito-borne disease caused by the chikungunya virus (CHIKV), an enveloped, single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the family Togaviridae, genus Alphavirus (2-4). The primary vectors are female Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes (Figure 1) (5). Humans are the main reservoir of CHIKV, whereas in Africa, non-human primates serve as the natural hosts, becoming infected through bites from forest-dwelling Aedes mosquitoes (4).

Figure 1: Aedes aegypti (left) and Aedes albopictus (right) mosquitoes (source: CDC) (6)

The first reported case in Foshan was identified as an imported case on July 8, 2025 (1), with no earlier potential cases detected, although the specific origin of importation could not be determined. This case may represent the index case. On July 9, 2025, a cluster of chikungunya fever cases was reported in Foshan city (7). Confirmation of all cases was achieved using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (7). Whole-genome sequencing of 190 confirmed cases classified all strains as belonging to the Central African Clade of the East-Central-South-African (ESCA) genotype (7).

Date of outbreak beginning July 9, 2025 (Official Outbreak Declaration)

Date outbreak declared over Ongoing outbreak

Affected countries and regions The primary affected region is Foshan City. The Foshan outbreak subsequently extended to 11 neighbouring cities within Guangdong Province through local mosquito transmission (7,8). Furthermore, imported cases linked to Foshan were reported in adjacent regions beyond Guangdong Province, including Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan (7).

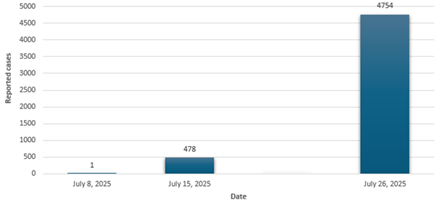

Number of cases (specify at what date if ongoing) There were limited data available documenting daily case numbers during the outbreak. An epidemic curve illustrating the precise incidence rate of the outbreak could not be produced due to limitations in data availability. However, publicly available sources indicated an unusual feature of the outbreak, characterised by a rapid increase in case numbers within one month (Figure 2). Since the first importation occurred on July 8, 2025, in Foshan City, Guangdong Province, the total reported cases had reached 478, and by July 26, this number had risen to 4,754 (Figure 2) (7,10,11).

In Foshan City, the daily reported cases peaked at 681 in July (7). Since mid-August, the outbreak has been brought under significant control through the implementation of effective measures, with daily reported cases declining to 100 (11).

Figure 2: Cumulative Reported Chikungunya Cases as of Selected Dates in Foshan City, China, July 2025 (7,10,11)

Clinical features

• The incubation period typically ranges from four to eight days but may vary between two and 12 days (2).

• Common clinical manifestations include acute onset of fever, accompanied by arthralgia, myalgia, headache, nausea, fatigue, and rash (2,5).

• Most chikungunya infections are symptomatic (approximately 85%), and the acute signs and symptoms resolve within two weeks (13). Asymptomatic infections account for approximately 3-28% of cases.

• Acute symptomatic infections are frequently misdiagnosed as other arboviral diseases with similar clinical presentations, such as Dengue and Zika (5,13).

• Most cases reported during the 2025 Foshan outbreak presented with mild symptoms (14).

Mode of transmission (dominant mode and other documented modes) CHIKV is primarily transmitted through the bites of infected mosquitoes. There is no documented evidence of direct human-to-human transmission via respiratory routes or casual contact (2). However, cases of chikungunya have been documented via bloodborne transmission (3) and vertical transmission (15). It is important to note that vertical transmission occurs primarily at the time of delivery, and CHIKV has not been detected in infants through breastfeeding (3).

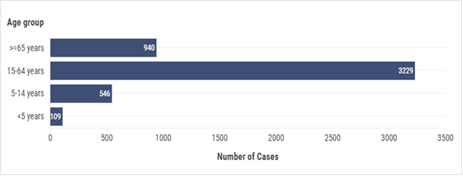

Demographics of cases Among confirmed cases in July during the Foshan chikungunya outbreak, the largest proportion occurred in individuals aged 15 to 64 years, followed by adults aged 65 years and older (Figure 3). Confirmed cases were identified using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The attack rate among children, particularly those under 5 years, appeared to be substantially lower than in adults, at approximately 2.3%. Children aged 5 years to 14 years had an attack rate of approximately 11.3% (7). However, the surveillance method may have played a role in the case ascertainment.

Male cases were reported at nearly the same frequency as female cases, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:0.97 (7).

Figure 3: Distribution of Confirmed Cases by Age Group During the Chikungunya Outbreak in Foshan, China, July 2025 (7)

Case fatality rate No deaths had been documented during the Foshan outbreak as of August 27, 2025 (14). Chikungunya is generally associated with a low case fatality rate; however, depending on the endemic setting and the vulnerability of specific risk groups, reported rates have ranged from less than 1% to 11.9% (16,17). Risk groups include newborns exposed during childbirth, adults over 65 years, and individuals with underlying conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or heart disease (18).

Complications Limited data are available documenting complications associated with the current outbreak. Based on prior outbreaks, the primary complication associated with CHIKV infection is persistent arthropathy, reported in 50% to 80% of cases, which may last for months to years and, in some cases (32%), progress to a debilitating inflammatory rheumatoid disease (13). Additional complications include hospitalisation (2%), liver disease (1%), shock or organ failure (3%), myocarditis (0.1%), and neurological manifestations (1%), such as encephalitis.

Haemorrhagic manifestations are rare, and Guillain-Barré syndrome has been reported in fewer than 1% of cases (13,19).

Available prevention The primary strategy for preventing CHIKV transmission is protection against mosquito bites, particularly through standard precautions for vector-borne disease during the infectious period to reduce onward transmission. The primary vectors, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, are typically active during daylight hours and can transmit CHIKV both indoors and outdoors. Therefore, the use of insecticide-treated netting (ITN) and window screens is especially recommended for individuals who remain indoors during the day. Additional protective measures include wearing clothing that minimizes skin exposure and applying insect repellents containing approved active ingredients at effective concentrations.

Environmental control strategies, such as regularly emptying water containers and disposing of waste, are essential to reduce mosquito breeding sites. On a broader scale, eliminating breeding habitats and the strategic use of insecticides within a radius of less than 100 meters around affected areas are recommended for systematic control (2,3).

In addition to standard vector control measures, China has adopted experimental and ecological strategies during the management of the Foshan chikungunya outbreak (20). One such approach involves the intentional release of Toxorhynchites mosquitoes, commonly referred to as “elephant mosquitoes”. These mosquitoes do not bite humans but prey on the larvae of Aedes mosquitoes, thereby reducing the vector population capable of transmitting CHIKV. Additionally, larvivorous fish species have been introduced into urban lakes and ponds to disrupt mosquito breeding cycles by consuming mosquito larvae (20).

Complementing these ecological interventions, a stringent containment protocol adapted from practices during the COVID-19 pandemic has been implemented. This includes the isolation of confirmed chikungunya cases in hospital settings equipped with mosquito-proof infrastructure, where patients remain quarantined until they test negative for the virus (20).

Several candidate vaccines are currently under clinical investigation, including a whole-virus inactivated vaccine, a VEE/CHIKV chimeric vaccine, a recombinant adenovirus-vectored vaccine, a DNA-based vaccine, and a virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine (5). More recently, mRNA-based vaccines have also become available. The currently approved vaccine for CHIKV infection is Ixchiq (VLA1553), a live attenuated vaccine authorized in the United States. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved updated labelling due to emerging concerns regarding its safety profile (21). Another promising candidate, PXVX0317, is under regulatory review and may receive approval in 2025 (22).

Available treatment The treatment of CHIKV infection is primarily symptomatic, with a focus on relieving acute-phase symptoms using anti-inflammatory medications. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), such as methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine, commonly used in the management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), have also been employed to alleviate persistent arthralgia in chikungunya patients. However, their efficacy remains limited, despite the clinical similarities between persistent arthralgia and RA (6). Several therapeutic agents are currently under clinical trials, including favipiravir, ribavirin, interferon alpha, umifenovir, suramin, and monoclonal antibodies (22). Non-steroidal medications should be avoided until dengue can be ruled out (23).

Comparison with past outbreaks The 2025 Foshan chikungunya outbreak represents the largest outbreak ever reported in China, with the cumulative number of cases in Guangdong Province reaching 9,933 by mid-August (24,25). Before this outbreak, the largest recorded outbreak in China occurred in two other cities in Guangdong Province, Dongguan and Yangjiang, where only 253 cases were documented over 40 days (26). Since the first identified case in 2008, a total of 94 imported cases and 425 locally acquired cases were reported in China up to 2019 (27).

Globally, CHIKV outbreaks have escalated markedly in both frequency and severity since 2004. Travel-related transmission, as observed in the Foshan outbreak, has also been documented in Italy (2007), France (2012), and the Americas (2013), highlighting the role of international mobility in the global spread of CHIKV. By 2025, the Americas reported the highest number of CHIKV cases, with Brazil accounting for 141,436 cases as of June 2025 (4).

Unusual features

• A substantially higher number of cases was observed in this outbreak compared to previous chikungunya outbreaks in China.

• Foshan City experienced a prolonged period of elevated temperatures exceeding 36 °C, with 13 days recorded in July, compared to 9 days in 2024 and 10 days in 2023 (28). Additionally, extreme rainfall reached 284.70 mm in July, surpassing historical levels observed in the previous two years (28).

Critical analysis

• Human travel is a major driver of chikungunya outbreaks globally. Since 2004, outbreaks originating in Kenya have spread to the Indian Ocean islands and subsequently to India, causing substantial epidemics worldwide. Before 2004, outbreaks were sporadic in Asia and Africa and typically limited in scale (29). The Foshan outbreak began with an imported case from an unidentified region, which seeded local transmission. Guangdong Province, characterized by high population density and frequent human movement, provided favourable conditions for rapid spread.

• Enhanced viral fitness may have contributed to the Foshan outbreak. The Foshan outbreak was caused by Clade 2 of the ECSA lineage (7). This clade has previously been associated with key mutations (E1:A226V, E2:L210Q, and E2:I211T) that enhance adaptation to Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, increasing transmission potential in outbreaks elsewhere (30).

• Natural infection with CHIKV typically induces a long-lasting antibody response that can persist for several months, and in some cases, years, protecting against reinfection. Most individuals infected with CHIKV develop neutralizing antibodies that target the E2 glycoprotein of the virus, thereby blocking viral entry into host cells (31). This immunological mechanism has likely played a role in interrupting transmission in some island populations, where extensive infection resulted in community-wide immunity (2). As Chikungunya is not endemic in China, and prior introduction of the virus by travellers has resulted in limited outbreaks, a lack of prior immunity in the local population permitted a significant escalation of chikungunya cases in Foshan. Due to the infrequent and limited nature of outbreaks in the past, which have been efficiently controlled through vector control and non-pharmaceutical interventions, there has been little need to enhance population immunity via vaccination. However, If the frequency and magnitude of outbreaks increase, a vaccination strategy will need to be considered.

• Environmental conditions further contributed to transmission. Southern China, including Guangdong Province, experienced rainfall during the monsoon season, creating abundant standing water for Aedes albopictus breeding (32). These ecological factors likely amplified vector density and facilitated CHIKV spread.

Key questions

1. What other factors have contributed to the significant surge in chikungunya cases in Foshan, compared to previous outbreaks in China?

2. Is a vaccine currently being used to control the outbreak?

3. What strategies can be employed to induce population-level immunity in China, aside from natural infection?

4. Are other arboviruses currently circulating in the region?

5. What is the current distribution and density of Aedes mosquito vectors across China?

Data availability statement: Outbreak data were collected from publicly available sources.

Ethics Statement: This Watching Brief did not involve human participants or animal research; therefore, ethics approval was not required.

Acknowledgement: Pan Zhang is supported by and acknowledges the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship and Microsoft Accelerating Foundation Models Research (AFMR) grant program. Dr Bari and Dr Quigley are supported by the Microsoft Accelerating Foundation Models Research (AFMR) grant program.

1. Tee KK, Mu D, Xia X, Explosive chikungunya virus outbreak in China, International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2025; 161,108089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2025.108089.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Chikungunya. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya; April 14, 2025; accessed August 23, 2025.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Transmission of Chikungunya Virus. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/chikungunya/php/transmission/index.html; December 6, 2024; accessed August 23, 2025.

4. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Factsheet for health professionals about chikungunya virus disease. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya/facts/factsheet; accessed August 23, 2025 .

5. de Lima Cavalcanti TYV, Pereira MR, de Paula SO, Franca RFdO. A Review on Chikungunya Virus Epidemiology, Pathogenesis and Current Vaccine Development. Viruses. 2022; 14(5):969. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14050969 .

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s Most (un)Wanted Mosquitoes. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/dengue/stories/unwanted-mosquitoes.html; May 29, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

7. Li Y, Jiang S, Zhang M, et al. An Outbreak of Chikungunya Fever in China - Foshan City, Guangdong Province, China, July 2025. China CDC Wkly. 2025 Aug 8;7(32):1064-1065. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2025.172 .

8. Wood R: Taiwan reports first imported chikungunya case from China. 9News. Available at: https://www.9news.com.au/world/taiwan-reports-first-imported-chikungunya-case-from-china/0162a4d0-5c50-44d9-bf87-3986ec6f3723; August 11, 2025; accessed August 23, 2025 .

9. Lewis A: China Reports Over 7,000 Chikungunya Cases in Guangdong Province Amid Aggressive Containment Efforts. Contagion. Available at: https://www.contagionlive.com/view/china-reports-over-7-000-chikungunya-cases-in-guangdong-province-amid-aggressive-containment-efforts; August 7, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

10. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Epidemic and emerging disease alerts in the Pacific as of 19 August 2025. Reliefweb. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/map/world/epidemic-and-emerging-disease-alerts-pacific-19-august-2025; August 19, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

11. South China’s Foshan confirms 1,873 cases of chikungunya, all mild: officials. Global Times. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202507/1338817.shtml; July 20, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

12. Gong W: Chikungunya daily cases in Foshan fall to 100. China News. Available at: https://m.chinanews.com/wap/detail/ecnszw/heummsh1679107.shtml; August 19, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

13. Hua C, Combe B. Chikungunya Virus-Associated Disease. Curr Rheumatol Rep 19, 69 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0694-0 .

14. Qiu Q: Foshan ends emergency response to Chikungunya outbreak as cases drop. China Daily. Available at: https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/618967; August 27, 2025; accessed September 4, 2025 .

15. Ferreira F, da Silva, ASV, Recht J, et al. Vertical transmission of chikungunya virus: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16, e0249166 .

16. Torales M, Beeson A, Grau L, et al. Notes from the Field: Chikungunya Outbreak — Paraguay, 2022–2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023; 72:636–638. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7223a5 .

17. Mavalankar D, Shastri P, Bandyopadhyay T, et al. Increased mortality rate associated with chikungunya epidemic, Ahmedabad, India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008 Mar;14(3):412-5. doi: 10.3201/eid1403.070720 .

18. Defence Health Agency. PUBLIC HEALTH REFERENCE SHEET Chikungunya Virus Disease. Available at: https://ph.health.mil/cdt/cphe-cdt-chikungunya-ref.pdf; December 13, 2023; accessed August 24, 2025 .

19. Kharwadkar S, Herath N. Clinical Symptoms and Complications of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya Infections in Pacific Island Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.2024 Feb 10; Preprint. 34 (2). pp. 1-23 https://repository.fnu.ac.fj/id/eprint/4337/ .

20. Newey S: China deploys ‘cannibal’ mosquitoes and killer fish to fight chikungunya. The Telegraph. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/china-deploys-cannibal-mosquitoes-to-fight-chikungunya/; August 8, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

21. US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Update on the Safety of Ixchiq (Chikungunya Vaccine, Live). Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/fda-update-safety-ixchiq-chikungunya-vaccine-live; August 6, 2025; accessed September 4, 2025 .

22. Abdelnabi R, Jochmans D, Verbeken E, et al. Antiviral treatment efficiently inhibits chikungunya virus infection in the joints of mice during the acute but not during the chronic phase of the infection. Antiviral Res. 2018 Jan; 149:113-117. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.09.016 .

23. Wijewickrama A, Abeyrathna G, Gunasena S, Idampitiya D. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) on bleeding and liver in dengue infection. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016 April;45(1):19-20. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.077 .

24. Liu LB, Li M, Gao N, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the chikungunya outbreak in Ruili City, Yunnan Province, China. J Med Virol. 2022 Feb;94(2):499-506. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27302 .

25. Pouille J: China deploys all available resources to tackle major chikungunya outbreak. Le Monde. Available at: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/environment/article/2025/08/26/china-deploys-all-available-resources-to-tackle-major-chikungunya-outbreak_6744719_114.html#:~:text=China-,China%20deploys%20all%20available%20resources%20to%20tackle%20major%20chikungunya%20outbreak,the%20mainland%20two%20weeks%20earlier; August 26, 2025; accessed September 4, 2025 .

26. Wu D, Wu J, Zhang Q, et al. Chikungunya outbreak in Guangdong Province, China, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 Mar;18(3):493-5. doi: 10.3201/eid1803.110034 .

27. Xi C: Imported Mosquitoes to Blame? Guangdong Reports 478 Cases of Chikungunya Fever – No Specific Cure or Vaccine. People News. Available at: https://www.peoplenewstoday.com/news/en/2025/07/16/1109843.html; July 16, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .

28. He C, Li G, An T. Climate, urbanization, and infectious disease: Environmental drivers of Foshan's chikungunya outbreak. Eco-Environment and Health. 2025; 4(4):100179. doi:10.1016/j.eehl.2025.100179 .

29. Mourad O, Makhani L, Chen LH. Chikungunya: An Emerging Public Health Concern. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2022;24(12):217-228. doi: 10.1007/s11908-022-00789-y .

30. Ramphal Y, Tegally H, San JE, et al. Understanding the Transmission Dynamics of the Chikungunya Virus in Africa. Pathogens. 2024; 13(7), 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens13070605 .

31. Chandley P, Lukose A, Kumar R, et al. An overview of anti-Chikungunya antibody response in natural infection and vaccine-mediated immunity, including anti-CHIKV vaccine candidates and monoclonal antibodies targeting diverse epitopes on the viral envelope. The Microbe. 2023 November 8; (1): 100018 .

32. Cash J, Woo R: Monsoon peaks in south China, unleashing landslides, disease. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/monsoon-peaks-south-china-unleashing-landslides-disease-2025-08-06/; August 6, 2025; accessed August 24, 2025 .